About Us

With the remarkable attention being paid to STEM education nationally, with the growing engagement of universities and colleges in STEM education reform, and with the proliferation of STEM education centers assisting universities to achieve these STEM education reforms, we are now positioned to create a potentially transformative form of infrastructure: a network of STEM education centers.

The present effort grows out of pilot work from APLU, which convened STEM education center directors with funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation in 2013. APLU invited centers that focus on undergraduate STEM education transformation because the association regularly convenes presidents, provosts, and other academic leaders who are seeking solutions to improve undergraduate STEM education. Because centers are a locus of educational change on campuses, they are positioned to serve as unique and powerful agents to address the calls for scaling and sustaining educational change (Olson & Riordan, 2012; Singer, Nielsen, & Schweingruber, 2012). Centers act as catalysts to link programs within an institution providing breadth of impact and attention, serve as vertical integrator within an institution (linking administration to on-the-ground programs), and connect as horizontal integrators across institutions.

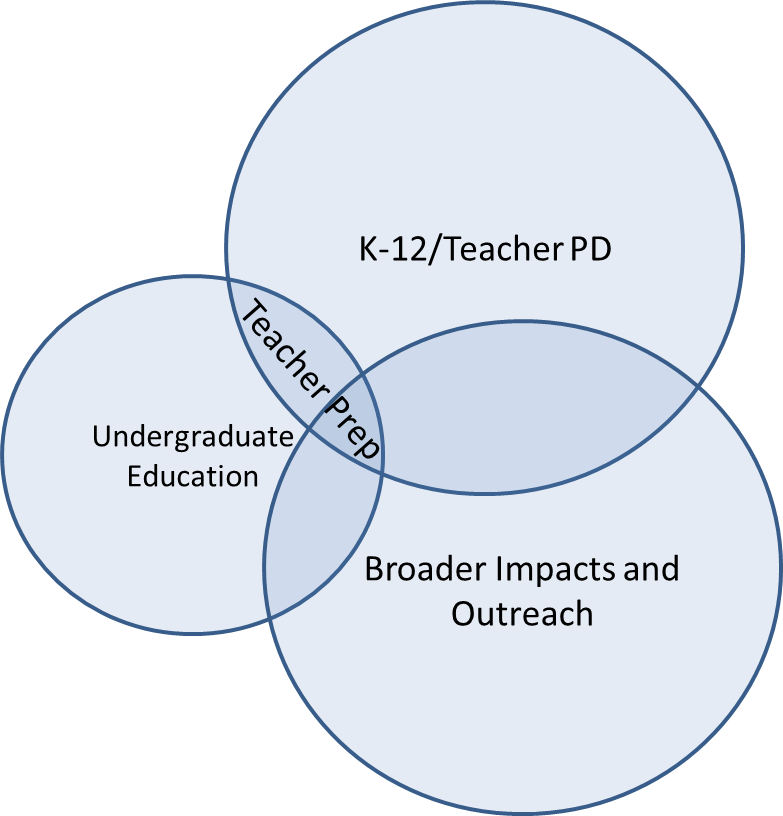

Figure 1. The Network of STEM Education Centers

engages leaders and “netweavers” who diffuse

information between the network and the larger community

working to improve the undergraduate STEM experience.

The Need for a Network of Centers

Individual centers (or directors of such centers) are seeking community – to share ideas; identify effective approaches; develop, import and export programs and people; and establish a sense of collective identity and legitimacy. We are building a network that supports and catalyzes these centers to help solve a perennial problem in STEM education reform: translating research into practices that will spread, be adapted, and sustained. This project will seed the development of a network and provide programming and resources for established and nascent centers such as: conferences, learning communities, online engagement platform, toolkits of resources, and directory of centers for the community and external stakeholders.Because no formalized network of STEM education centers exists, the current effort will address calls from the White House (Olson & Riordan, 2012) and National Academies (Singer et al., 2012) for such multi-institutional / nation-wide approaches. Uniquely, this network serves those centers that have a focus on STEM education and undergraduate transformation within individual colleges and universities.

Our pilot work, demonstrated the breadth of centers, interest in the formation of national network, and potential for such a network as catalyzing agent and research venue (Riordan, 2014). To date we have engaged 124 centers at 108 institutions and have identified 207 centers at 163 institutions. Sixty-nine centers have completed extensive profiles on a national website and another 31 centers have profiles in progress. We have launched a listserv of 196 directors and staff.

We propose to catalyze a STEM education center network by facilitating meetings that employ a variety of communication channels (including an online community platform) to foster ongoing access and exchange of information. Our work is modeled after successful scientific and practitioner networks (Goldstein & Butler, 2010a,b; Goldstein, Wessells, Lejano,& Butler, 2013) and successful networks supporting change in STEM instruction operating at the faculty level (Narum & Manduca, 2012; Henderson, Beach, & Finkelstein, 2011; Kezar & Gerhke, 2014). Where possible we draw on research that examines the social network construct with regard to change in higher education (Kezar, 2014). We are focused on opportunities to learn, communicate and share, and develop leadership. Our goal in this activity is to catalyze a learning network that becomes self-sustaining.

The broad array of potential outcomes from building the network include:

- incubating, supporting, and empowering individual centers across the US;

- a new national network (even possibly a national association of centers);

- and new resources for addressing key identified challenges in STEM education transformation (such as retention, participation, and public endorsement of STEM education).

Pilot Work – demonstrating need and capacity to build the network

We have held three meetings with the directors of STEM education centers (September 2013, October 2014, and June 2015 with 167 participants from 100 centers). These meetings established a first cohort of leaders, identified interest and needs for an ongoing community or network, and created a public online presence for the community addressing the priority need to learn more about other centers. Participants concluded that the next step is to build a community that can share ideas, practices, and resources through on-line mechanisms and convene when needed to address specific topics. In addition to enhancing the capacities of universities to address challenges in STEM education, participants identified some high needs areas and capacities of centers that could foster communication and collective action. These themes will be the scaffold for our discussions:

- Retention and success: How are STEM education centers driving retention and success, especially in the first two years of undergraduate education?

- Quality education: How are STEM education centers training and evaluating faculty teaching and shaping learning outcomes for STEM majors including STEM teachers?

- Research and assessment: How are STEM education centers contributing to disciplinary based education research (DBER), evaluating student learning, and driving assessment to support STEM education improvements?

- Partnerships beyond the university: How are STEM education centers partnering with K-12 schools, 2 and 4-year colleges and universities, and/or state networks (e.g. Battelle’s STEMx), and industry.

- Engaging Faculty: How are STEM education centers effectively engaging faculty? Is it through reform of upper division courses, outcomes for majors, benchmarking against peer departments, or other methods?

- Broadening Participation: How are STEM education centers expanding access to and success in STEM education for students from under-represented communities?

As an example of interest in these thematic approaches, we have received funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation to hold a workshop in 2015 to explore innovative and effective ways to engage the majority of faculty at research intensive institutions (with a focus on the senior tenure-line chemistry and physics faculty) in pedagogical reform. The workshop will be held immediately following the national STEM education centers conference.

A Focus on Centers that are Engaged in Undergraduate STEM Education Reform

Analysis of the exiting center profiles helps map the objectives of centers interested in forming a community (Figure 2). While many centers have multiple foci, two larger groups focus on teacher preparation/K-12 partnerships and broader impacts, and a smaller group of centers serve undergraduate STEM education reform. Existing associations of STEM education centers either do not address the needs of this latter group or try to address the entire range of objectives. Given that shared identity in a network is an essential component of success (Wenger, 1998; Goldstein and Butler, 2010a,b), we have chosen to build a network of centers whose focus is on undergraduate STEM education reform. Having a tightly focused agenda where centers with similar missions can share successes and challenges is the key to building a robust network. At the same time, we will create strong ties to overlapping communities in the K12 and Broader Impacts worlds.

Figure 2. STEM education center types and emerging networks

Synergy with other Communities, Networks, and Associations

We are drawing on insights from other efforts such as:

- APLU’s Science and Mathematics Teaching Imperative (SMTI) has been addressing, in part, the needs of centers engaged in teacher preparation through the SMTI National Conference.

- The National Alliance of Broader Impacts (NABI), formerly known as BIONIC, serve centers that identify most closely with a broader impacts mission.

- The Professional and Organizational Development (POD) Network in Higher Education is devoted in part to improving teaching and learning.

- The Bay View Alliance is a network of nine institutions seeking to promote change across higher education.

- The AAU STEM education initiative is promoting undergraduate change among their network.

- PKAL is dedicated to empowering STEM faculty to graduate more STEM students, and

- The Reinvention Center is a national consortium of research universities strengthening undergraduate education.

This STEM Education Centers Network will also complement efforts from disciplinary and professional societies and others that have more targeted focus and communities, or do not engage centers directly. In this effort, we will bring leadership from these other key networks and will draw from their models of what works to ensure synergy rather than competition and to enhance the capacity of all networks.

References

Olson, S. & Riordan, D. G. (2012). Engage to Excel: Producing One Million Additional College Graduates with Degrees in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Report to the President. Executive Office of the President.

Singer, S. R., Nielsen, N. R., & Schweingruber, H. A. (Eds.). (2012). Discipline-based education research: Understanding and improving learning in undergraduate science and engineering. National Academies Press.

Riordan, D.G. (2014). STEM education centers: a national discussion. APLU/SMTI Paper 8. Washington, DC: Association of Public and Land-grant Universities.

Goldstein, B. E. & Butler, W. H. (2010a). Expanding the scope and impact of collaborative planning: combining multi-stakeholder collaboration and communities of practice in a learning network. Journal of the American Planning Association, 76(2), 238-249.

Goldstein, B. E. & Butler, W. H. (2010b). The US Fire Learning Network: Providing a narrative framework for restoring ecosystems, professions, and institutions. Society and Natural Resources, 23(10), 935-951.

Goldstein, B. E., Wessells, A. T., Lejano, R., & Butler, W. (2013). Narrating resilience: transforming urban systems through collaborative storytelling. Urban Studies, 0042098013505653. Available at: http://usj.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/10/08/0042098013505653.abstract

Narum, J. and Manduca, C. (2012). Workshops and Networks in Bainbridge, W. S. (Ed.). (2011). Leadership in science and technology: A reference handbook. Sage Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-7688-6 p. 443-451

Henderson, C., Beach, A., & Finkelstein, N. (2011). Facilitating change in undergraduate STEM instructional practices: an analytic review of the literature. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(8), 952-984.

Kezar , A. & Gehrke, S. (2014). Lasting STEM Reform: Sustaining Non-Organizationally Located Communities of Practice Focused on STEM Reform. Paper prepared for the 2014 ASHE Annual Conference, Washington, DC

Kezar, A. (2014). Higher Education Change and Social Networks: A Review of Research. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(1), 91-125.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge university press. Goldstein, B. E. & Butler, W. H. (2010a). Expanding the scope and impact of collaborative planning: combining multi-stakeholder collaboration and communities of practice in a learning network. Journal of the American Planning Association, 76(2), 238-249.

Goldstein, B. E. & Butler, W. H. (2010b). The US Fire Learning Network: Providing a narrative framework for restoring ecosystems, professions, and institutions. Society and Natural Resources, 23(10), 935-951.

Stay Connected

X (formerly Twitter)

Facebook

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS